Reverse Engineering GOES-16 CDA Telemetry

In this post, I’ll detail how I managed to reverse engineer the telemetry signal from GOES-16 — NOAA’s third generation geosynchronous weather satellite built by Lockheed Martin and launched into space by ULA’s Altas V rocket.

This satellite is mostly known by the HRIT signal, responsible to distribute high-resolution meteorological data to hundreds of institutions throughout the portion of the earth illuminated by the spacecraft. Including the famous full-disk images with the resolution of 250 meters per pixel. Besides the HRIT and telemetry, it also transmits other signals (e.g. DCPR and GRB) which will be discussed in the future.

This project was made with Open Source Software. For the decoding part of I’ll be using Open Satellite Project software developed originally for the LRIT Signal and for the demodulation part GNU Radio Companion. The decoder and demodulator are available on GitHub.

Feasibility

The telemetry signal from previous GOES generations is known for not being encoded. This means that a very high SNR is needed to successfully decode the CCSDS Transfer Frames into the final data. Luckily this generation uses two types of coding that lowers the SNR needed to an amateur level.

The telemetry modulation of this generation has also changed. Now the signal is modulated with BPSK instead of QPSK. This is a good thing because we can reuse the demodulator software from HRIT. The frequency also changed to 1693.0 MHz which is very close to the HRIT signal. In fact, you can capture both of them at the same time using an RTL-SDR.

Receiving & Demodulating

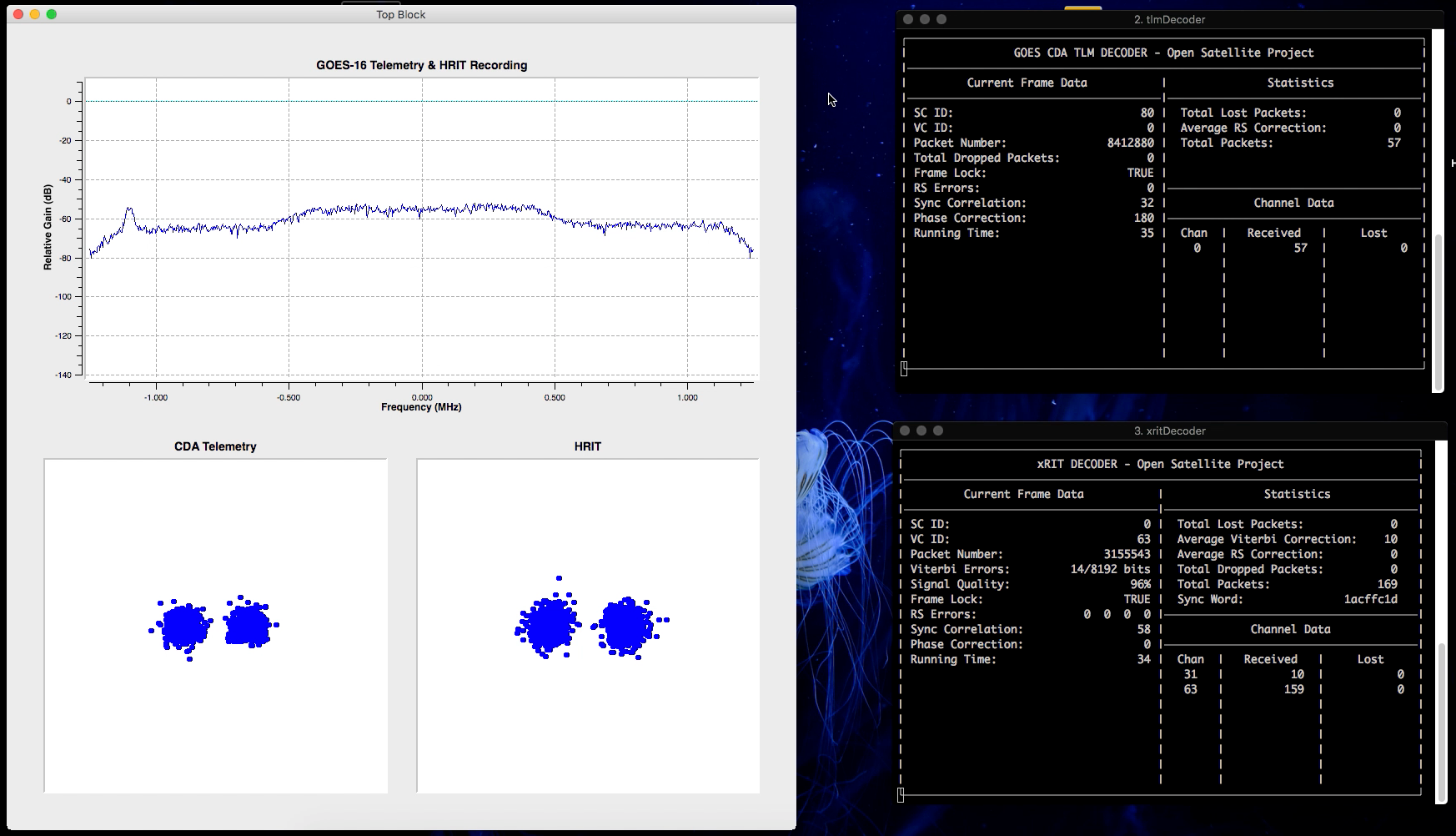

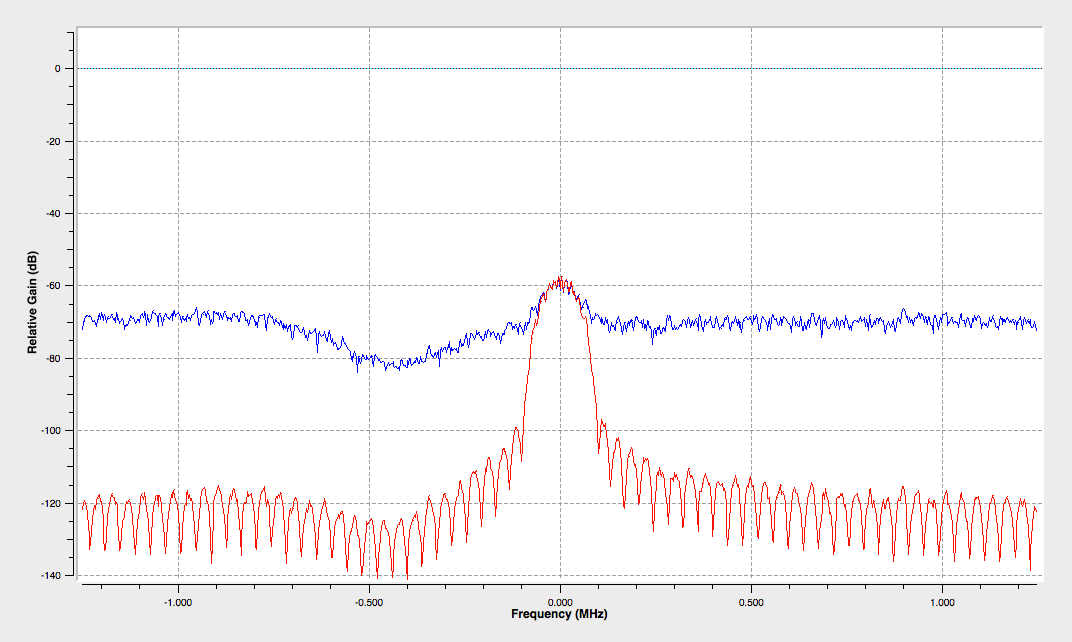

The first step is to receive and filter the actual signal from the noise floor. Here I’m using a 2.5 MHz baseband recoding provided by Lucas Teske that can be downloaded from his website. You can easily record the signal with the same hardware used for the HRIT signal. In the screenshot below, you can see the entire baseband recoding in blue and the actual signal filtered by a Root Raised Cosine Filter Block in red.

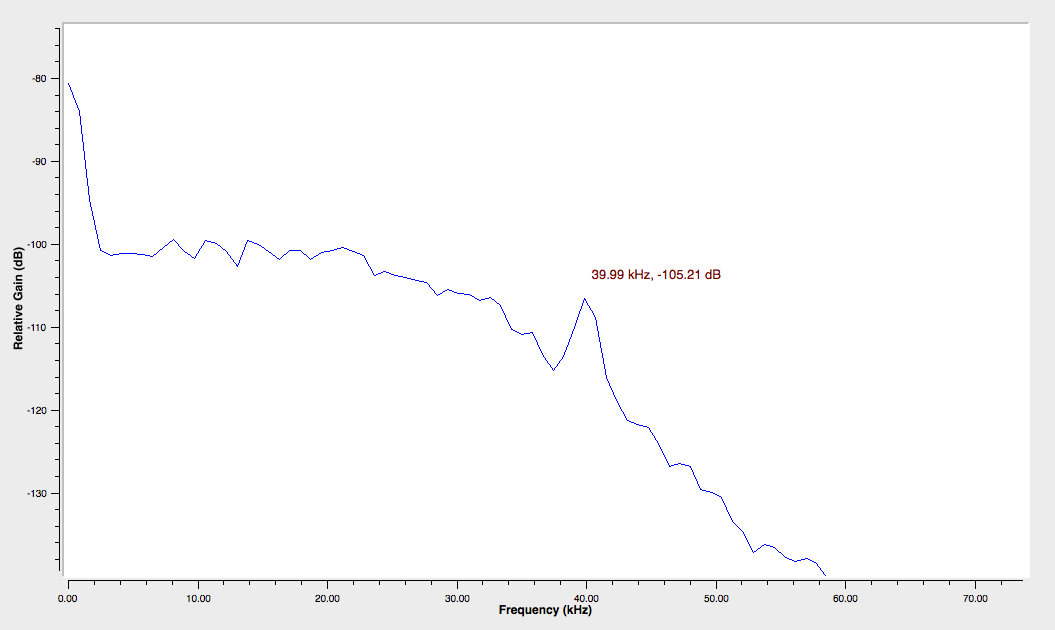

It can be easily identified as PSK modulated just by looking at the FFT. This type of modulation is widely used by L-Band spacecraft. Phase Modulation is also very common (e.g. HRPT) but they have a characteristic central carrier. I used the Cyclostationary Analysis technique to discover the signal symbol rate. With this technique, you multiply the signal with the delayed version of itself. The symbol rate will magically pop-out in the resultant graph. In this case, the symbol rate is 40 kilo-symbols per second.

The last step of the demodulation part is to apply the specifications we got into the standard BPSK demodulator and send the binary stream to the Decoder via the standard TCP Sink. The GNURadio Companion file used to reverse engineer the signal can be downloaded here. And the production companion file can be found on the Project’s GitHub Repository. This will be ported to the stock Open Satellite Project demodulator in the near future.

Decoding

I couldn’t find any detailed documentation of this signal anywhere on the internet. The only specification I found was the final bitrate of 32 kbps. By subtracting that from the total signal baud rate we get 8 kbps. This is the bandwidth used by the coding, suggesting that no Convolutional Encoding is being used, as they are known by using a lot of bandwidth. When received, no apparent structure is visible, suggesting that the data is coded.

After some experimentation with the decoder, I saw the standard CCSDS framing structure. Turns out that the data is encoded with the same Differential Coding used by the HRIT signal. More specifically the Non-Return-to-Zero Mark (NRZM). The Open Satellite Project differential decoder expects hard bits coming from the Viterbi decoder. Therefore, a casting from soft to hard symbols is needed between the TCP Source and the decoder. This is fine because the soft symbols are just useful to the Convolutional Decoder find the most probable path in the Markov Sequence.

// Convert soft to hard bits.

for (int i = 0; i < FRAMEBITS; i += 8) {

uint8_t byte = 0x00;

for (int j = i; j < i + 8 && j < FRAMEBITS; j++)

byte = (byte << 1) | ((codedData[j] < 128) ? 0x00 : 0x01);

decodedData[i/8] = byte;

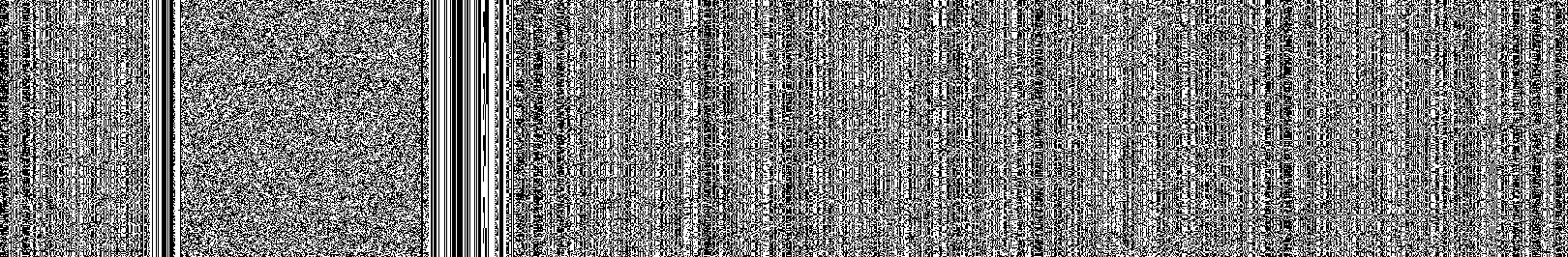

}After decoding, the three structures from the CCSDS Transfer Frame are visible in the bit-viewer. A 32 bits sync word, the payload data, and one Reed-Solomon block. The CCSDS Standard states that one RS Block is needed after 223 bits. Therefore, the frame size is 256 bits instead of 1024 bits from the HRIT frame with four RS Blocks.

You can notice that the sync word isn’t at the beginning of the frame. This has to be corrected by measuring the correlation of the encoded word with every frame and perform the synchronization. For that, we will use the same correlation algorithm from the HRIT software with some modifications. The number of encoded words still two, accounting for the NRZM bit-swap. But the word length changed from 64 bit to 32 bit, since there is no 1/2 Convolutional Encoding. The Python code used to encode each word with NRZM are shown below. This code was made by Lucas Teske for the GOES-16 HRIT Patch.

# Hex Word: 0x1ACFFC1D

# Binary Word: 0b00011010110011111111110000011101

# NRZ-M Word (Normal): 0b00010011011101010101011111101001

# NRZ-M Word (Bitflip): 0b11101100100010101010100000010110

# NRZ-M Normal Hex: 0x137557E9

# NRZ-M Bitflip Hex: 0xEC8AA816

bword = "00011010110011111111110000011101"

lastbit = "1"

encodedbword = "";

for i in bword:

if lastbit != i:

encodedbword += "1"

lastbit = "1"

else:

encodedbword += "0"

lastbit = "0"

print(encodedbword);

The frame is now synchronized and can be de-randomized by the same polynomials used by the HRIT. They are specified by the CCSDS standard. To save CPU the sync word is deleted from the rest of the frame. Now we run the Reed-Solomon algorithm to identify and correct any error with the frame. Finally, the data is corrected and ready for the demuxing part that will process the CCSDS Transfer Frame into the final data.

Next up: Demuxing

The demuxing part isn’t completely figured out yet. Lack of public documentation regarding the inner layer of the data field forces us to reverse engineer it from scratch. This isn’t a trivial situation because the telemetry data isn’t predictable. I will talk about it in the next post. Follow me on Twitter @luigifcruz to get the latest updates. The decoder and demodulator are available on GitHub. Big thanks to @usa_satcom and @lucasteske for the support.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.

Member discussion